Vatican II on Atheism: A More Fruitful Dialogue

by Stephen Bullivant

Filed under Atheism

Welcome to the second post in my little series 'Vatican II on atheism'. As noted last time, according to at least one reputable commentator, the Council's primary statement on the subject "may be counted among [its] most important pronouncements". In future posts, we'll be looking at Gaudium et Spes 19-21, as well as the separate statement on salvation in Lumen Gentium 14-16, in some details. So - let's face it—we've all got plenty of exegetical fun to look forward to. This post, though, will be rather different. Its purpose is to set the scene, to explain the contexts out of which GS 19-21 and LG 14-16 grew. Think of it as being akin to a classic "How the Gang Got Together" episode.

Fact is, atheism could easily not have featured in the conciliar literature at all. The Council opened in October 1962. By the start of the Third Session, two years later, the most any of the draft documents had to say on the subject was a passing mention of "errors which spring from materialism, especially from dialectical materialism or communism" in the so-called 'Schema XIII'. Just 15 months before the close of the Council, then, one of "the most serious matters of our time"—as Schema XIII (i.e., the ultimate Gaudium et Spes) would come to describe it—wasn't looking quite so serious after all.

A combination of two things changed that: the bishops, and the Pope (which, incidentally, is exactly the right combination you want making things happen at an Ecumenical Council).

Among many other criticisms of the Schema XIII draft as a whole, its ignoring of atheism was time and again singled out in the bishops' plenary discussions. On the very first day of debate, the Chilean Cardinal Silva Henríquez spoke of "the need for dialogue with contemporary humanism", urging that "The Church must try to comprehend atheism, to examine the truths which nourish this error, and to be able to correspond its life and doctrine to these aspirations." The next day, the Belgian Cardinal Suenens had this to say:

"Atheism is certainly a terrible error...it would be too easy simply to condemn it. It is necessary to examine why so many men profess themselves to be atheists, and whom precisely is this 'God' they so sharply attack. Thus dialogue should be begun with them so that they may seek and recognize the true image of God who is perhaps concealed under the caricatures they reject. On our part, meanwhile, we should examine our way of speaking of God and living the faith, lest the sun of the living God is darkened for them." [These are my translations from the official Acta; for full translations of the speeches, see Peter Hebblethwaite, The Council Fathers and Atheism: The Interventions at the Fourth Session of Vatican Council II (New York: Paulist Press, 1967)]

Taking these comments (and many more on other topics) on board, the Council Fathers duly sent Schema XIII away to be rewritten. A new version—the so-called 'Ariccia text' for Vatican II buffs—was circulated the following summer, and met with much greater, general approval in the September 1965 debates. But yet again, the Fathers proved sticklers when it came to the statement on atheism; though much improved, it still wasn't up to scratch.

In the most powerful of the critiques, the Melkite Cardinal Maximos Saigh warned that atheists "are often scandalized by the sight of a mediocre and egoistical Christendom absorbed by money and false riches", adding: "is it not the egotism of certain Christians which has caused, and causes to a great extent, the atheism of the masses?" In the end, the Cardinal Archbishop of Vienna, Franz König, suggested that—with the close of the Council only months away—a whole new statement on atheism should be written from scratch. Helpfully, he offered the services of the newly-created Secretariat for Non-believers for this eleventh-hour mission. Which brings us nicely to Pope Paul VI...

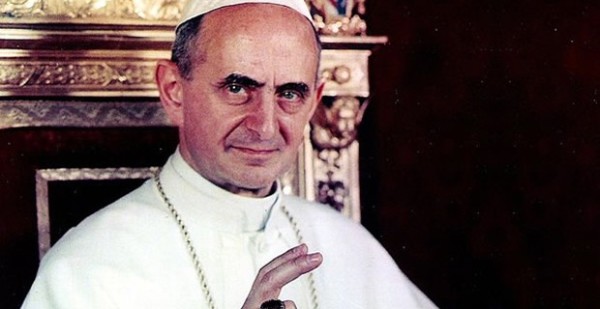

Paul was the second of Vatican II's popes, having been elected following the death of John XXIII in June 1963. The following August, he published his first encyclical Ecclesiam Suam, in order to show how and why the Church and the world, as he rather sweetly puts it, "should meet together, and get to know and love one another" (art. 3). 'Dialogue' is the great watchword here, and much attention is given to the value of improving relationships with both non-Catholic Christian communities, and the other world religions. Crucially, atheists are not ignored either.

Paul's opening gambit might not, I readily admit, exactly warm the cockles of the hearts of my atheist friends here at Strange Notions. However, my aim here is not to 'cherry pick' the enticing, welcoming bits of the Church's engagement with unbelief (like you wouldn't see straight through that, right?). So here is what he actually says:

"Many [today] subscribe to atheism in one of its many different forms. They parade their godlessness, asserting its claims in education and politics, in the foolish and fatal belief that they are emancipating mankind from false and outworn notions about life and the world and substituting a view that is scientific and up to date. This is the most serious problem of our time. [...] Any social system based on these principles is doomed to utter destruction. Atheism, therefore, is not a liberating force, but a catastrophic one, for it seeks to quench the light of the living God." (Ecclesiam Suam, 99, 100)

There are a good few paragraphs more in this vein, for those wanting to read them. It becomes clear that the communist regimes of the Soviet Union and elsewhere—and the sufferings of Christians at their hands—are a large part of what Paul has in mind here. But I won't pretend that he explicitly confines his remarks to them alone.

In a certain sense, the above remarks make what Paul goes on to say about atheists all the more significant.

"We see these men serving a demanding and often a noble cause, fired with enthusiasm and idealism, dreaming of justice and progress [...] They are sometimes men of great breadth of mind, impatient with the mediocrity and self-seeking which infects so much of modern society. They are quick to make use of sentiments and expressions found in our gospel, referring the brotherhood of man, mutual aid, and human compassion. Shall we not one day be able to lead them back to the Christian sources of these moral values?" (Ecclesiam Suam, 104)

In my own atheist days, I suppose that I would have found something patronising and presumptuous in those words, not least on the subject of meta-ethics (and perhaps a part of me still does). I like to think, though, that I would have recognized at least as much sincerity and goodwill on the Pope's behalf (however much I thought him misguided on major points), as he is willing to grant to those unbelievers dreaming of 'justice and progress' (however much he thinks them misguided on major points). What do you think?

Paul ends his comments on atheism by expressing hope for "the eventual possibility of a dialogue between these men and the Church, and a more fruitful one than is possible at present" (art. 105). This hope was evidently a sincere one. Eight months later, in April 1965, the Vatican newspaper quietly announced Paul's creation of a Secretariat for Non-Believers. As its new secretary explained to Vatican Ratio, its purpose was not only to study atheism, but also "to organize groups of priests and lay people who will be well prepared to enter into a dialogue with atheists, should the occasion arise" (quoted in my The Salvation of Atheists, p. 70). As its president, Cardinal König, used playfully to point out, the Secretariat was named for non-believers, and not against them.

As mentioned earlier, it was the Secretariat's consultors who ended up drafting Vatican II's Gaudium et Spes 19-21. It's this we'll being looking at next time around. I made a point in my last post, though, of ending with a quotation from an actual atheist. While I doubt I'll manage to maintain that tradition for the whole series, here's another one.

It comes from a letter I dug up in the Secretariat's archives, now housed at the Pontifical Council for Culture, about five years ago. It was written by Tolbert H. McCarroll, Executive Director of the American Humanist Association, to Cardinal König, and is dated just five days after the Secretariat was formally announced. McCarroll welcomes this fact, explains a bit about the AHA (enclosing some literature), and cordially invites members of the Secretariat to meet with humanist representatives in the Netherlands that summer. He ends with sentence:

"This letter would not be closed without reference to the late Pope John XXIII. We may differ in our opinion as to the source of his humane concern, but we can join together in our admiration of this great model of humanity."

Pope Paul's desire for a "more fruitful dialogue" seemed like it might come true rather sooner than he had hoped.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.