Moral Relativism, Conscience, and G.E.M. Anscombe

by Joe Heschmeyer

Filed under Objective Morality

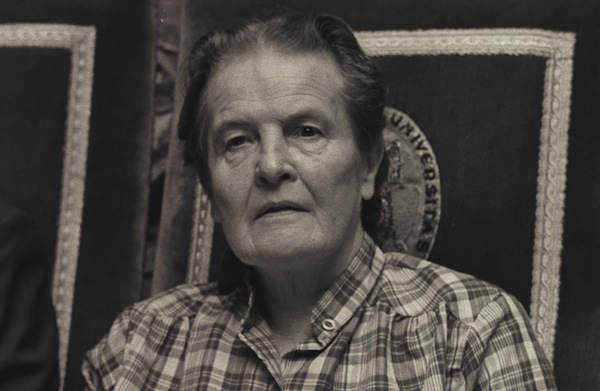

What should we make of the proposal that there's no such thing as objective morality, that morals are just determined by cultures or by individuals? That's what I'd like to address in this post. I specifically engage the cultural relativism advocated by Ruth Benedict, who claimed that “good” and “evil” are socially determined. I argue instead for the moral absolutism advocated by the British Catholic analytical philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe (G.E.M. Anscombe).

This post will proceed by considering the appeal of, and arguments for moral relativism; the arguments against moral relativism; and the interplay between moral relativism and Anscombe's moral philosophy on the question of conscience.

The Appeal of Moral Relativism

The rise of moral relativism is closely related to the process of globalization. In earlier times, when individuals were exposed primarily or exclusively to their own cultures, it was easy to imagine that one's culture's morals simply reflected morality. The spread of Christianity throughout Europe (and Islam throughout much of the rest of the world) had a similarly homogenizing effect on morality: pagan mores gave way to an Abrahamic moral code that held largely intact from one nation to another. What was immoral in France was likely immoral in Scotland, Spain, and Switzerland as well. This moral uniformity lent itself strongly to the suggestion that these mores reflected the natural law, that these were objective rules of morality existing apart from any particular culture.

As Christianity's influence on European and North American culture waned, this uniformity began to break down. Simultaneously, anthropologists, sociologists, and historians began to examine cultures with moral systems dramatically distinct from, and even diametrically opposed to, Christian culture. For example, anthropologist Ruth Benedict argues against moral objectivity by telling stories about the (allegedly) paranoid and violent culture on Dobu island in northwest Melanesia, a culture that she described as treating violence as acceptable, while ostracizing the kind and helpful.1 In the light of these alien moral codes, what had once looked like common-sense moral rules reflecting a universal human consensus now appeared to be arbitrary social conventions. The cultural relativist argues on this basis that the notion of an objective and transcultural morality is illusory.

Instead, the argument goes, we must learn to value tolerance, since to insist upon Christian morality would be an arrogant imposition of our own culture. Certainly, the morals on Dobu seem barbaric and evil, but Benedict argues that “the very eyes with which we see the problem are conditioned by the long traditional habits of our own society.”2 That is, we see Dobu morality as wicked because we approach it with Western eyes. They would likewise see Western morality as wicked, given their own cultural formation.

The Problem with Moral Relativism

Without question, G.E.M. Anscombe, whose adherence to moral absolutism is well-established, would reject moral relativism of this sort. Francis J. Beckwith gives several reasons why in answering the above line of argumentation. First, this cultural relativism conflates preference-claims with moral-claims, so that “killing people without justification is wrong” is treated as a merely subjective preference, like “I like vanilla ice cream.”3 Second, relativism is premised off of the idea that, since cultures cannot agree on what objective morality is, there must be no objective morality. Logically, the conclusion does not hold: the people of Dobu might have cosmological and scientific beliefs radically at odds with Western cosmology and science, but we would not rationally conclude that, therefore, there must be no objective cosmology or science. Worse, if the mere existence of disagreement means that the belief is not objectively true, then the disagreement over cultural relativism disproves it.4 Third, the cultural relativists typically exaggerate the disagreements between cultures, and ignore underlying commonalities between moral codes.

Additional problems with cultural relativism can be seen from the real-life encounter of General Sir Charles James Napier, British Commander-in-Chief in India from 1849 to 1851, with certain Hindu priests. The priests were protesting the British ban on Sati, the practice of burning a widow alive on her husband's funeral pyre. They argued that Sati “was a religious rite which must not be meddled with,” and “that all nations had customs which should be respected and this was a very sacred one.”5 Napier responded:

"Be it so. This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pyre. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs."6

Napier's response highlights several problems facing cultural relativism. Where cultures clash, whose moral code should triumph? For the British to “tolerate” Sati would involve violating their own moral codes. For that matter, whose morals should triumph within a particular culture? Should the Indian brides simply “tolerate” being thrown into the flames against their wills because of popular morality? Or should cultural morality simply be decided by the powerful imposing their will—be that the Indians forcing brides onto the pyre, or the British forcing them to stop? Quickly, this devolves into pure Nietzschean will to power.

As Beckwith notes, “cultural relativism is making an absolute and universal moral claim, namely, that everyone is morally obligated to follow the moral norms of his or her own culture.”7 This is problematic, both in that it is self-refuting (since the crux of cultural relativism is the rejection of such absolute moral claims) and that it would eliminate any possible social progress, since no one could upset the moral norms of his or her own culture. For that matter, the whole notion of social progress would have to be rejected, since “progress” implies some comparison of a culture to an external standard of some kind.8

Moral Relativism and the Problem of Conscience

That moral relativism cannot be endorsed in total does not mean that it is entirely without merit. Take, for instance, this claim by Ruth Benedict:

"The concept of the normal is properly a variant of the concept of the good. It is that which society has approved. A normal action is one which falls well within the limits of expected behavior for a particular society. Its variability among different peoples is essentially a function of the variability of the behavior patterns that different societies have created for themselves, and can never be wholly divorced from a consideration of cultural institutionalized types of behavior."9

As a description of the good, this account is inadequate, for the reasons discussed above. However, as a description of the influence of societies in the formation of individual consciences, it highlights a real phenomenon. In Anscombe's words, “it belongs to the natural history of man that he has a moral environment,” such that it is impossible to raise a child without this being the case.10 This moral environment includes the deliberate influence of the child's parents, but it also includes the society in which the child is raised. A child raised in the notoriously-violent Yąnomamö culture will be shaped differently than a child raised in a strictly-pacifistic Quaker community, and their approach towards moral reasoning will likely reflect this upbringing, at least initially. Benedict and the cultural relativists are right, therefore, to see culture as playing an indispensable role in the formation of individual consciences.

In fact, Anscombe and Benedict arrive at similar conclusions for the class of cases that Anscombe would describe as involving “invincible ignorance,” which she defines as “ignorance that the man himself could not overcome.”11 Thus, if Abner has been taught of a certain affirmative duty, and Charles has never been taught about this (and has no reason to suspect its existence), Abner is morally responsible for his failure to perform the duty, while Charles is not. For Benedict, this distinction would be explained by reference to the differing cultural norms facing Abner and Charles. For Anscombe, it would be explained by reference to Charles' invincible ignorance. Nevertheless, the conclusion would reached along somewhat similar lines: because the two men received different moral instructions, they are held to differing standards.

Here, the agreement between Anscombe and Benedict ceases. In two major areas, they would decisively part company on the question of conscience. The first is on the relationship of social moral pedagogy to objective morality. Benedict viewed it as disproving the existence of objective morality, at least in any transcultural sense: that is, because cultures indoctrinate in differing, and even contrary ways, there can be no binding transcultural morality. Anscombe would disagree, holding that some societies are simply better or worse at moral formation, just as some parents are. Both parents and the culture possess a certain moral authority in the upbringing of children, yet Anscombe noted that this authority “is not accompanied by any guarantee that someone exercising it will be right in what he teaches.”12 Acculturation and indoctrination must therefore be compared to an external standard of objective morality. Accordingly, we can affirm that some parents or cultures create a moral environment suitable for raising virtuous individuals, while others fail to do so, or succeed in creating viscous persons.

The second area of disagreement between Anscombe and Benedict on the question of conscience involves the degree to which the individual's socially formation is fixed. Certainly, Benedict speaks of cultural morality as a static thing: an individual believes such-and-such because these are the values of his culture. As Beckwith notes, the rigidity of such a view leaves no room for moral reformers like the leaders of the Civil Rights movement.13 Nor does it seem to leave room for individuals like Benedict herself, whose belief in cultural relativism was a radical break from her native culture's moral outlook. Anscombe rightly rejects Benedict's rigid view, holding instead that an individual may move closer to (or further from) objective morality throughout his life. She describes the context in which children come to reject their parents' moral authority; the same is surely true of societies.14 Individuals need not live out their entire lives blindly accepting a particular thing as true simply because society says so.

These two points prove to be crucial. Because conscience can be malformed, the individual may face a genuine moral perplexus in which every course of action is morally wrong:

"If you act against your conscience you are doing wrong because you are doing what you think wrong, i.e. you are willing to do wrong. And if you act in accordance with your conscience you are whatever is the wrong that your conscience allows, or failing to carry out the obligation that your conscience says is none."15

This moral perplexus is only comprehensible in light of the fact that relativism is wrong. We would otherwise have to affirm that “there's no such thing as false conscience. Conscience is conscience and infallibly tells you what is right and what is wrong. So conscience always binds, or else legitimately leaves you morally free to do or not do.”16

So, having rejected moral relativism, we are left facing a moral perplexus. Here, it is important that Benedict was mistaken to view socially-formed conscience as static or fixed. It is precisely in the ability of the conscience to be formed, even in adulthood, that Anscombe finds a solution to the perplexus, saying: “There is a way out, but you have to know that you need one and it may well take time. The way out is to find out that your conscience is a wrong one.”17 That is, the long-term solution to the perplexus problem is to repair the damage inflicted upon your conscience, whether that damage was self-inflicted or the result of a bad moral environment.

Conclusion

A major appeal of moral relativism is that it tells a half-truth: culture really does influence the way that individuals approach morality. A proper moral environment is invaluable, if not indispensable. But this reality does not point to the absence of objective morality. Rather, as Anscombe shows, it points to the need of properly forming one's conscience, and ensuring a healthy moral environment for the rearing of children. To fail to take these steps risks placing you or your children in a moral perplexus, in which every possible action is morally wrong.

Related Posts

Notes:

- Ruth Benedict, “A Defense of Moral Relativism,” in Do the Right Thing: Readings in Applied Ethics and Social Philosophy, 2nd Edition, ed. Francis J. Beckwith (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning, 2002), 9. ↩

- Ibid., 6. ↩

- Francis J. Beckwith, “A Critique of Moral Relativism,” in Do the Right Thing: Readings in Applied Ethics and Social Philosophy, 2nd Edition, ed. Francis J. Beckwith (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning, 2002), 13. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- William Napier, History of General Sir Charles Napier's Administration of Scinde (London: Chapman and Hall, 1851), 35. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Beckwith, “A Critique of Moral Relativism,” 17. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Benedict, “A Defense of Moral Relativism,” 10. ↩

- G.E.M. Anscombe, “The Moral Environment of the Child,” in Faith in a Hard Ground, ed. Mary Geach and Luke Gormally (Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic, 2008), 224. ↩

- G.E.M. Anscombe, “On Being in Good Faith,” in Faith in a Hard Ground, ed. Mary Geach and Luke Gormally (Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic, 2008), 111. ↩

- G.E.M. Anscombe, “Authority in Morals,” in Faith in a Hard Ground, ed. Mary Geach and Luke Gormally (Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic, 2008), 93. ↩

- Beckwith, “A Critique of Moral Relativism,” 17. ↩

- Anscombe, “Authority in Morals,” 94. ↩

- G.E.M. Anscombe, “Must One Obey One's Conscience?,” in Human Life, Action and Ethics, ed. Mary Geach and Luke Gormally (Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic, 2005), 241. ↩

- Ibid., 239. ↩

- Ibid., 241. ↩

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.