Lying and Truth-Telling: A Question for Catholics and Atheists

by Deacon Jim Russell

Filed under Morality

EDITOR'S NOTE: Today begins a three-part series on the morality of lying. Our first post comes from Jim Russell, a Catholic deacon. Tomorrow, we'll hear from Patheos atheist blogger James Croft. And Thursday, Catholic blogger Leah Libresco will wrap it up.

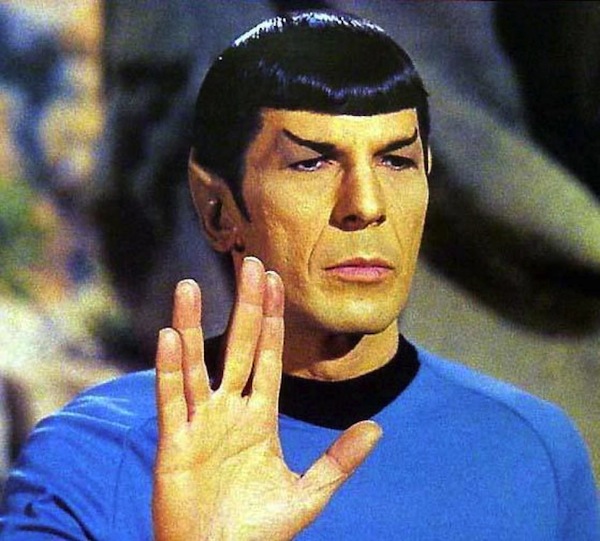

Have you seen the newest Star Trek film, the second of the “re-boot” of the franchise? In it, Mr. Spock reminds Captain Kirk of a particular Vulcan trait—that Vulcans may never under any circumstances tell a lie—and then, by movie’s end, we witness the same Mr. Spock engage in a masterful bit of deception against a key villain, a deception that, of course, doesn’t involve any spoken falsehood, but one that proves just as effectively deceptive as any blatant lie.

Is this a contradiction? Can Vulcans be masters of deception just as long as they don’t say anything untrue?

Well, if you think Vulcans have an interesting perspective on what lying is and isn’t, wait till you consider how we humans have dealt with this issue for the last couple millennia or so.

Back in the day, long before followers of “The Way” (Christianity) came upon the scene, the morality of lying was a topic debated by ancient philosophers and left largely unresolved. Was it ever okay to lie? What really is a lie? One might have thought that, with the advent of the Catholic Church—and with it the “Magisterium” (the Church's official and Holy-Spirit-guided teaching authority)—such a debate might have been settled long ago—at least for Catholics, that is.

But sometimes the truth is indeed stranger than (science) fiction. And here is the truth: For two thousand years, the Catholic Church has left this question somewhat unsettled: whether or not all falsehoods spoken with the intention to deceive are immoral acts of “lying."

This in-house Catholic concern remains a legitimate theological debate, and it flares up occasionally in the Wild West of the Catholic blogosphere. Before we get into the details of the Catholic view of lying, though, let’s take a moment to mention a couple aspects of this issue that make it interesting to both atheists and Catholics.

First, the “societal” or “common-good” aspect of truth-telling is incontestable. Thus prohibitions against lying transcend anything religious or sectarian. The stability of human society really depends on the good will that ought to exist among individuals, and that common good can only be realized by truthfulness. Having said that, many questions remain about how this pursuit plays out among so many people with diverse moral perspectives.

Second, there is an “apologetic” aspect to this issue that really cuts both ways, relative to atheists, Catholics, and morality. The usual claims made—which I've seen several times in the Strange Notions comboxes—focus on the contrast between a moral system built upon moral “absolutes” (such as is found in the Catholic faith) and a moral system devoid of moral “absolutes” (such as is found among many, though not all, atheists).

Catholics often claim the moral “high ground” because the Catholic morality builds upon the foundation of the moral absolute. But, as we will see regarding lying, the Catholic system does not, in fact, pin everything down for us, put it in a box, wrap it in a bow, and leave it on our Catholic doorsteps merely to open up and “repeat as often as is necessary.” Far from it. Indeed, on many moral issues, such as lying, we Catholics find ourselves in a place similar to that of a “non-moral-absolute” non-believer: we’ve got to use our best individual judgement when making particular moral choices about truth-telling. In such a case, the moral “absolute” doesn’t give us a ready-made answer regarding how to behave in specific instances.

However, this also must mean that the atheist ought to concede that we Catholics are really not taught by Mother Church to merely check our intellects at the door and do whatever the moral checklist says we should (or should not) do. The truth is, from the Catholic view, the moral “absolute” is only part of the moral equation. Another part of that equation is all about properly forming conscience and then acting on that properly formed conscience. At the end of the day, we Catholics—just like our atheist friends—are called upon to apply concretely in our own lives what we have come to believe about right or wrong. The Church completely recognizes and respects the rights of conscience of its Catholic members.

So What Does the Church Really Teach About Lying?

The briefest of thumbnail sketches on the history of lying and Church teaching would go like this. The early Church’s embrace of the Ten Commandments yielded for us the “moral absolute” of the Eighth Commandment: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. This is bedrock. But, like another Commandment (Thou shalt not kill), it leaves much for us to reflect upon and properly interpret. The Early Church Fathers were not unanimous in their treatment of what it meant to “lie” and whether all “lying” was sinful. But St. Augustine wrote an important treatise on the subject titled “On Lying” in which he opined that all spoken falsehood with intention to deceive is immoral. Over time, many (but not all) theologians gravitated toward the Augustinian view—and his definition of lying. As did St. Thomas Aquinas, whose definition of lying, “speech at variance with the mind,” is a bit different but consonant with Augustine. What then emerges in the Church is what is known as the “common teaching of Catholic theologians” on the subject of lying.

But what is “common teaching”? It’s the common theological opinion (note “opinion” and not official magisterial teaching) of Catholic theologians and is most often taught in Church catechesis as the “safe” opinion upon which Catholics may form their consciences. In fact, the Augustinian view (the view shared by “Vulcans”) is that one must never “lie” under any circumstances. And it’s the “common teaching” of the Augustine/Aquinas perspective that is found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church today:

"A lie consists in speaking a falsehood with the intention of deceiving...By its very nature, lying is to be condemned. It is a profanation of speech, whereas the purpose of speech is to communicate known truth to others. The deliberate intention of leading a neighbor into error by saying things contrary to the truth constitutes a failure in justice and charity." (CCC 2482, 2485)

But for Catholics, the “common teaching” is not the only option for us. It’s definitely a “safe” way to live—never speaking a falsehood with intention to deceive under any circumstances. But the many cases in which we would seek, in defense of self or others, to employ deception against unjust aggressors, have caused others to take less rigorous views. One need only read Cardinal John Henry Newman’s essay on “Lying and Equivocation” to see that this debate retained nearly all its force well into the nineteenth century despite the existence of the Catholic “common teaching.” Even G.K. Chesterton famously said, “Every sane man knows he would tell a lie to save a child from Chinese torturers.”

So the debate over what is and isn’t lying continues among Catholic theologians (and bloggers) in our own time. The “common teaching” leaves Catholics with a safe alternative for most cases, but once we begin to consider how we should act when confronted with the famous “Nazi-at-the-door” or the “save-the-Starship-Enterprise-with-a-well-placed-falsehood” or the “undercover-narcotics-cop-infiltrating-the-drug-ring” or the “covert-spy-fighting-the-totalitarian-regime” or “future-pope-letting-a-fugitive-assume-his-priestly-identity-to-escape-the-country”—fill in the blank. We begin to see that the Catholic “common teaching” on lying is ultimately a work in progress.

Now, I do believe there is a future, thoroughly “Catholic” solution worth proposing (and I will propose one of my own in an upcoming book, God willing). But in the meantime, much may be gained and learned in opening up this subject to the many voices in the Strange Notions comboxes.

Is there something of value in the Catholic understanding of truth, the meaning and purpose of speech, the desire to form a trusting society built on the avoidance of the lie?

What might the atheist have to say about the nature of truth apart from God and what we might owe our fellow neighbors and friends when it comes to truth-telling?

Can Mr. Spock and St. Augustine come to a place of mutual agreement regarding what we should never do—speak a deceptive falsehood—from very different starting points? Or does Spock's deception via an artful "truth-telling" still constitute at lie at its core? What do you think of the Catholic “common teaching”? What non-theistic moral framework might suffice for helping guide us regarding when we might speak a falsehood, or not?

The questions abound and perhaps the answers will as well. Maybe the Catholic and the atheist will turn out to be not so very far apart on this one!

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.