Darwin’s Blind Spot

by Gerard M. Verschuuren

Filed under Evolution

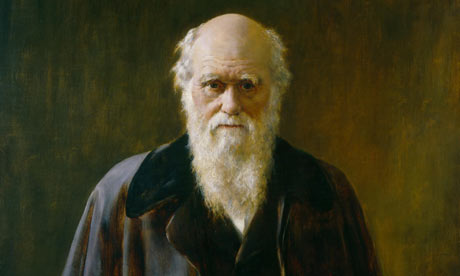

It is a well-known fact that Charles Darwin, the author of that famous, and at the same time infamous, book entitled On the Origin of Species, used to be all over the religious map during his lifetime (1809-1882). Darwin’s personal beliefs remain ambiguous. I think what expresses his ambiguity best is what he wrote in a letter to J.D. Hooker (1861): “My theology is a simple muddle; I cannot look at the universe as the result of blind chance, yet I can see no evidence of beneficent design, or indeed of design of any kind, in the details.”

Did Darwin ever become an atheist? Again, the evidence is rather ambivalent. Even if he did become an atheist, such may have happened after he developed his theory, but not necessarily because of his theory; in his own words, it was the devastating loss of his ten-year-old daughter Annie that made him an agnostic. However, being an agnostic or even an atheist would not really affect the validity of his evolutionary theory.

Where Did Darwin Go Astray?

It is not my intention in this article to analyze Darwin’s shortcomings in either biology or theology, but I do think there is a strong flaw in his philosophy, which may have been the ultimate cause that steered him in the wrong direction in terms of both his biology and his theology.

My starting point is one of the statements he makes in his autobiography. When he expresses his doubts about the claims theism makes, he says that the theory of natural selection makes him wonder whether “the mind of man, which has, as I fully believe, been developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animal, [can] be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions.” And again in a letter to W. Graham in 1881, “Would anyone trust in the convictions of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind?”

I would say Darwin does make a great point here: If the human mind is the mere product of natural selection, we cannot trust any of the conclusions it draws. Curiously enough, though, Darwin applies this insight only to any theological conclusions one might make but not to his own biological conclusions. He doesn’t seem to realize that when he discards theistic claims, he should also discard his own evolutionary claims, because he strongly believes that both are the mere product of natural selection.

It seems very obvious to me that even Darwin’s own theory of natural selection has run into trouble here, by cutting off our reason for reasoning, because once I take natural selection to be the only power shaping me and my mind—in the same way it shapes my DNA—I would have reason to doubt what my rational capacities are really worth. And evolutionary theory happens to be fully dependent on these very capacities—which fact gives it a rather shaky basis.

Somehow, as far as I know, Darwin never fully realized how serious this complication is. I call that Darwin’s “blind spot.” Darwin was not able, or perhaps not willing, to think outside the Darwinian box, so he missed out on the vast meta-physical territory located outside his physical box. Does this mean that his theory is in serious trouble? It is not, if we take his theory for what it is worth, but it is, if we stretch its scope beyond what it is supposed to cover. Let me explain.

Is Darwinism in trouble?

What Darwin did—and what made his evolutionary theory so revolutionary—is that he approached all aspects of life as natural phenomena, which are to be explained by natural causes and physical laws, embodied in objectively testable theories. He was right: If science does not go to its limits, it would be a failure. Thus, modern biology was born. I consider this a great part of Darwin’s legacy, but again, it may not be the end of the story.

Darwin’s theory would be in real trouble, though, if we lose sight of the fact that all scientific theories only achieve local successes that cannot claim any universal validity. Yet, Darwin gave his biological claims much more power than they actually had; he tried to give them universal validity. He claimed that his biological theory explained not only biological phenomena, but also all other phenomena outside the biological realm—such as sociology, psychology, and even religion. Darwin himself may not have explicitly done so, but his “disciple,” the philosopher Herbert Spencer, definitely did.

I think it’s needless to say that, in all such cases, the boundaries of the underlying theory are being grossly overstepped. Whenever this happens, we end up with an “ism,” an ideology similar to atomism, physicism, evolutionism, materialism, scientism, and so on. All “isms” tend to go overboard; they love to simplify the vast complexity of reality into a simple model; they replace reality with one of its specific maps.

Darwin Himself Is “More” Than a Product of Evolution

When he came up with the theory of natural selection, Darwin somehow didn’t realize that he was “more” than one of the products of natural selection. The philosopher Peter Kreeft, for instance, places this philosophical truth in the right context when he says that a projector must be “more” than the images it projects in the same way as a copy machine must be “more” than the copies it makes—or put in more general terms, the knowing subject must be “more” than the known object.

In a similar vein, when Darwin discovered the law of natural selection, he must have been “more” than the theory he discovered. If he were not, he would run into a serious problem of circularity. Even if the theory of natural selection in itself is not the product of natural selection, it still is a product of the human mind (Darwin’s, to be precise).

So I think we should come to an important conclusion: Even when they study the human brain as an object of science, scientists also need the human mind as the subject of science—for without the human mind, with its intellect and rationality, there would be no science at all. One would need a mind before one can study the brain! We have definitely entered meta-physical territory here—unfortunately located on Darwin’s “blind spot.”

Darwin could have cleared the confusion he had created for himself if he could just acknowledge that the human mind is not a product of natural selection. The human brain (including its intelligence) may be a product of natural selection, but that doesn’t mean the human mind (including its intellect) is too. As a matter of fact, the theory of natural selection must assume the human mind, but it can neither create it nor explain it. The brain cannot study itself; we do need a mind to study the brain. So the mind must have another origin than the brain. I would even go further and claim that the mind must be something made in God’s image, a take-off of the Creator’s mind.

Whereas it was Darwin’s conclusion that we cannot trust anything we know about God, I would rather argue the opposite—that we cannot trust anything we know at all if there were no God.

Related Posts

Note: Our goal is to cultivate serious and respectful dialogue. While it's OK to disagree—even encouraged!—any snarky, offensive, or off-topic comments will be deleted. Before commenting please read the Commenting Rules and Tips. If you're having trouble commenting, read the Commenting Instructions.